Historical evidence reveals that humans possess the remarkable ability to render certain physical appearances invisible if they do not focus on them, including something as fundamental as a color. Specifically, the color blue. While our eyes can perceive among approximately one million colors, it remains unclear how differently each person experiences them.

No, the ancients did not “fail to see the colour blue”. Nor the Himba, mentioned in the text. Both simply don’t assign the shades that you’d call “blue” in English to their own special colour word. Each language splits the colour space in different ways.

I’ll illustrate this with an example in the opposite direction - English using a single primary word for colour, while another language (Russian) uses two:

In Russian, those three are considered separated colours; they aren’t a hue of each other, goluboj is not sinij or vice versa, just like neither is zeljonyj. In English however you’d lump the first two together as “blue”, and the third one as “green”.

Does that mean that your typical English speaker fails to see one of the first two shades? No. And if necessary they might even use expressions to specify one or another shade, like “sky blue” vs. “dark blue”. They still lump them together as “blue” though, unlike Russian speakers, and they might not pay too much attention to those silly details.

dumbu - more saturated yellows, yellowish oranges, and extra saturated greens

burou - your run-of-the-mill green and blue

Now, check the colours that I posted with Russian terms. Just like English doesn’t care about the difference between two of them, Himba doesn’t care about the third one either.

There’s also an interesting case with Japanese, that recently split 青/ao and 緑/midori as their own colours. Not too much time ago, Japanese did the same as Himba, and referred to the colour of grass and the sky by 青/ao; however people started referring to the yellower hues of that range by 緑/midori (lit. “verdure”), until it became its own basic word.

That’s actually problematic for traffic legislation, because it requires the colour of traffic lights to be 青/ao, and people nowadays don’t associate it with green. Resulting into…

…cyan lights. They’re blue enough to fit the letter of the legislation, but green enough to be recognised as green lights!

Now, regarding specific excerpts from the text:

Gladstone noticed Homer described the sea color as “wine-dark,” not “deep blue,” sparking his inquiry.

Gladstone (and sadly, many people handling ancient texts) likely had the same poetic sensibility as a potato.

The relevant expression here is ⟨οἶνοψ πόντος⟩ oînops póntos; it’s roughly translatable as “wine-faced sea”, or “sea that looks like wine”. Here’s an example of that in Odyssey, Liber VII, 250-ish:

[245] Therein dwells the fair-tressed daughter of Atlas, guileful Calypso, a dread goddess, and with her no one either of gods or mortals hath aught to do; but me in my wretchedness did fate bring to her hearth alone, for Zeus had smitten my swift ship with his bright thunderbolt, [250] and had shattered it in the midst of the wine-dark sea.

Why would be Homer referring to the colour of the sea? It’s contextually irrelevant here. However, once you replace that “wine-dark” from the translation with “inebriating”, suddenly the expression makes sense, Homer is comparing the sea with booze! He’s saying that it’s dangerous to enjoy that sea, that you should be extra careful with it. (You could also say that the sea is itself drunk - violent and erratic).

The ancient Egyptians were the first to adopt a word to describe the color blue.

I’m really unsure if this is the exception that proves the rule (since the Egyptians synthesised a blue dye from copper silicate) or simply incorrect.

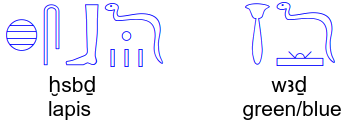

At least accordingly to Wiktionary, the word ḫsbḏ* refers to lapis lazuli (the mineral) and its usage for colour is non-basic (a hue). The actual primary word for what English calls “blue” is shared with what English calls “green”, and it would be wꜣḏ*.

No, the ancients did not “fail to see the colour blue”. Nor the Himba, mentioned in the text. Both simply don’t assign the shades that you’d call “blue” in English to their own special colour word. Each language splits the colour space in different ways.

I’ll illustrate this with an example in the opposite direction - English using a single primary word for colour, while another language (Russian) uses two:

In Russian, those three are considered separated colours; they aren’t a hue of each other, goluboj is not sinij or vice versa, just like neither is zeljonyj. In English however you’d lump the first two together as “blue”, and the third one as “green”.

Does that mean that your typical English speaker fails to see one of the first two shades? No. And if necessary they might even use expressions to specify one or another shade, like “sky blue” vs. “dark blue”. They still lump them together as “blue” though, unlike Russian speakers, and they might not pay too much attention to those silly details.

That’s basically what Himba speakers do, except towards all three of them. Here’s how the language splits colours:

You could approximate it in English as:

Now, check the colours that I posted with Russian terms. Just like English doesn’t care about the difference between two of them, Himba doesn’t care about the third one either.

There’s also an interesting case with Japanese, that recently split 青/ao and 緑/midori as their own colours. Not too much time ago, Japanese did the same as Himba, and referred to the colour of grass and the sky by 青/ao; however people started referring to the yellower hues of that range by 緑/midori (lit. “verdure”), until it became its own basic word.

That’s actually problematic for traffic legislation, because it requires the colour of traffic lights to be 青/ao, and people nowadays don’t associate it with green. Resulting into…

…cyan lights. They’re blue enough to fit the letter of the legislation, but green enough to be recognised as green lights!

Now, regarding specific excerpts from the text:

Gladstone (and sadly, many people handling ancient texts) likely had the same poetic sensibility as a potato.

The relevant expression here is ⟨οἶνοψ πόντος⟩ oînops póntos; it’s roughly translatable as “wine-faced sea”, or “sea that looks like wine”. Here’s an example of that in Odyssey, Liber VII, 250-ish:

[245] ἔνθα μὲν Ἄτλαντος θυγάτηρ, δολόεσσα Καλυψὼ ναίει ἐυπλόκαμος, δεινὴ θεός: οὐδέ τις αὐτῇ μίσγεται οὔτε θεῶν οὔτε θνητῶν ἀνθρώπων. ἀλλ᾽ ἐμὲ τὸν δύστηνον ἐφέστιον ἤγαγε δαίμων οἶον, ἐπεί μοι νῆα θοὴν ἀργῆτι κεραυνῷ [250] Ζεὺς ἔλσας ἐκέασσε μέσῳ ἐνὶ **οἴνοπι πόντῳ**Murray translated that as “wine-dark”:

Why would be Homer referring to the colour of the sea? It’s contextually irrelevant here. However, once you replace that “wine-dark” from the translation with “inebriating”, suddenly the expression makes sense, Homer is comparing the sea with booze! He’s saying that it’s dangerous to enjoy that sea, that you should be extra careful with it. (You could also say that the sea is itself drunk - violent and erratic).

I’m really unsure if this is the exception that proves the rule (since the Egyptians synthesised a blue dye from copper silicate) or simply incorrect.

At least accordingly to Wiktionary, the word ḫsbḏ* refers to lapis lazuli (the mineral) and its usage for colour is non-basic (a hue). The actual primary word for what English calls “blue” is shared with what English calls “green”, and it would be wꜣḏ*.

*in hieroglyphs: