That style does work well for presentations

I honestly prefer presentations to writing for the reasons you pointed out. I have never been too nervous when it comes to public speaking, and I feel much more able to convey my point through a more conversational style. However, my presentation style (specifically slide design) has had to change a lot over the course of my career.

When I was in grad school, my preferred method of presentation was to have a slide with a single graph/image/diagram on it and then verbally talk through all the things I wanted to convey for that slide. It allowed me tons of flexibility, kept the slides from becoming cluttered and distracting, and created a more conversational atmosphere as people felt more empowered to ask questions as I was going (this also helps keep the audience engaged).

However, as I moved into a professional setting, I had a mentor sit me down and tell me how great my presentations were, but they were not really effective in a corporate setting like this one (global company, split across timezones, etc). The simple reason being that the slides I was making were being shared to others who couldn’t make it to my presentation and a good chunk of the actual audience of the presentation only ever got to see the slides, without the benefit of my talking to help them understand. So, this has led me to move more towards including text on my slides. I basically have to ask myself if there is enough information on this slide to understand things without my explaining it, but without anything extra to make it confusing.

Since the pandemic, I have also had to change things up a bit to make presentations more amenable to presenting via Teams/Zoom. This means things like removing videos, complex animation, or any audio. It just doesn’t work reliably enough through screen sharing and if you can find a way around it, then it makes everybody’s life easier.

Speaking of tangents, this has been a long one, but I care a lot about effective communication and specifically presentations. So many people are so bad at giving a good presentation, and I find it frustrating personally, when I have to sit through so many.

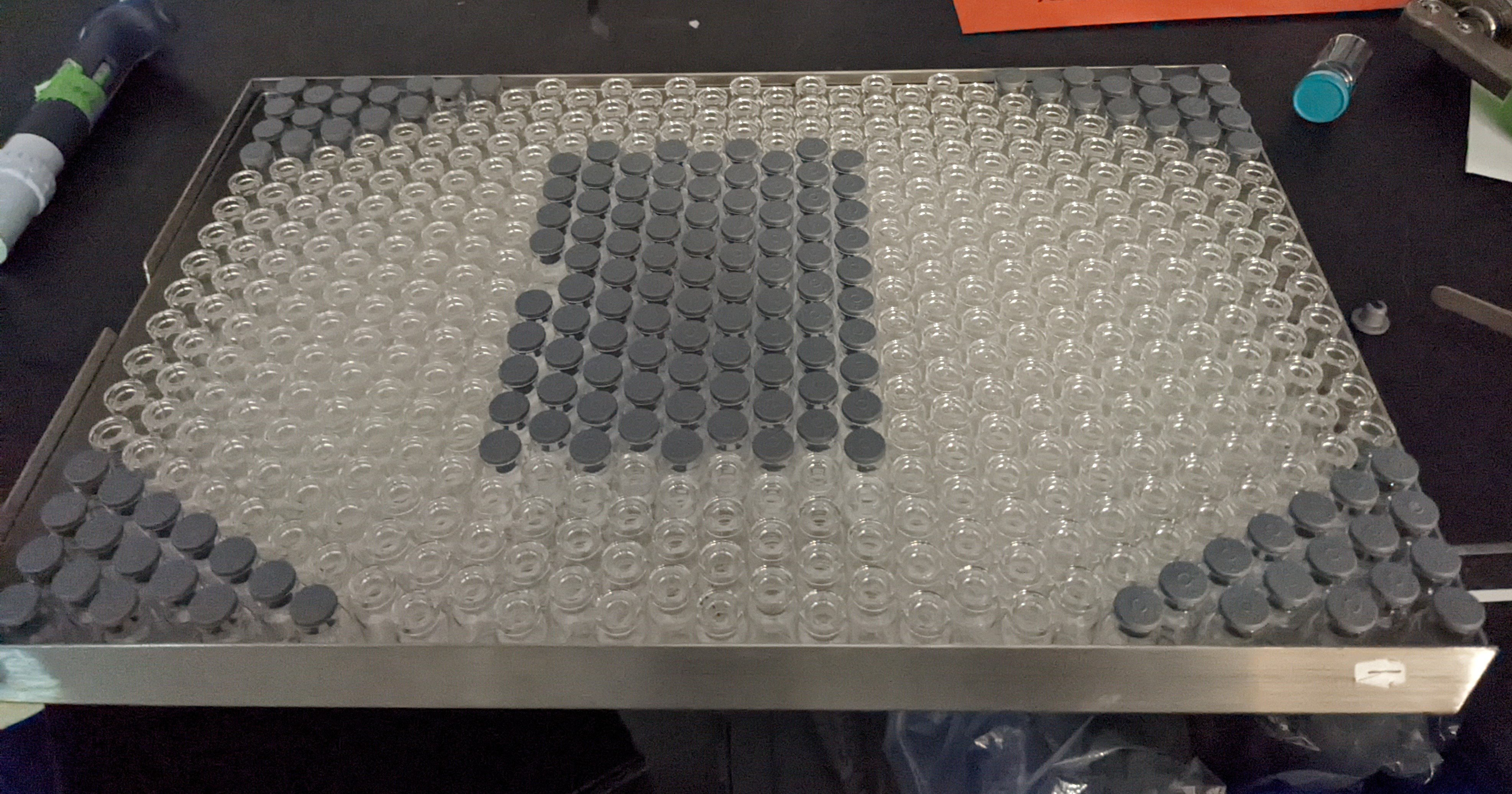

I work in pharma, regularly writing and filing things with the FDA (and other agencies), and this has been a topic of conversation at work. The good news for people is that the EMA is still a thing in the EU. So, at least the large pharma companies (like the one I work for), are likely to not really change much about their quality control/processes/etc. because we will still need to conform to the EMA guidelines which are typically in line with the current FDA (sometimes more strict, sometimes less so). The real quality concern would be smaller companies that only file for products in the US. They would only need to meet whatever new FDA guidelines come into effect (if they even do, changing stuff like GMP guidance is extremely complicated and time consuming) since the US is their only market.